Allergies: How Can Pets Avoid Them?

- Dr Andrew Matole, BVetMed, MSc

- May 31, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 4, 2022

Most itchy dogs and cats need some medical attention and this can be time-consuming, expensive and sometimes with side effects. Itches that are caused by parasites are curable but generally, itchy skins do not resolve without treatment. If your pet is scratching, an immediate visit to the vet is most advisable. Unfortunately, allergies usually need lifelong care as they are not easily cured. Avoiding the trigger for the itch is much the best solution and when this is achieved it is all that is needed sometimes. In other cases, it aids their medical treatment such that less medication is needed which may mean lower costs and fewer side effects.

What is an allergen?

Allergens are substances that trigger an allergic reaction – an abnormally strong immune response that causes damage to the body. Common allergens for dogs are parts of house dust mites, pollen, food proteins and flea saliva. Mould spores, fabrics and the dander of other species (feathers, wool, cats) are less common allergens.

How do allergies happen?

The mechanism of allergies is such that the immune system identifies non-parasitic foreign substances such as pollen, mould, animal dander, or food mistakenly as harmful. These substances at this point are referred to as allergens and end up causing a condition called allergy that causes reactions in the mucosa, skin, gastrointestinal tract, airways, and blood vessels resulting in symptoms like urticaria, dermatitis, oedema, asthma, etc. When they get into the body, they are referred to as antigens. The antigens are divided into three types:-

Exogenous antigens

Endogenous antigens and

Autoantigens.

An exogenous antigen is an antigen that enters the body via inhalation and ingestion. An endogenous antigen is one that is produced within the body due to an infection. An autoantigen is a protein that is recognized and attacked by the immune system only due to genetic and environmental factors. The allergens stimulate the immune system cells (plasma and mast cells) to release certain biochemical substances, such as histamine, which then lead to allergy symptoms or an allergic reaction referred to as anaphylaxis, anaphylactic reaction or anaphylactic shock.

Fig. 3: An infographic showing the stages of an allergic reaction.

Which dogs benefit from allergen avoidance?

Allergen avoidance is the best and most effective intervention for animals with a flea allergy, adverse reactions to food (food allergy) and contact allergy. Allergen avoidance is sometimes possible and may be useful for dogs with atopic dermatitis as well as allergic conjunctivitis and rhinitis.

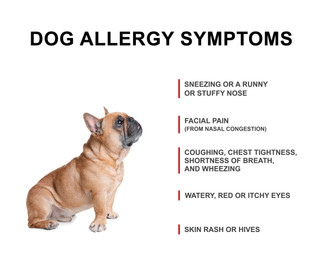

Fig. 4: An infographic showing foods causing food allergy and allergy symptoms in dogs

Atopic animals may have a component of adverse reaction to food allergens, if so avoiding these foods will be beneficial, and should reduce the anti-inflammatory medication load required to control the concurrent atopic dermatitis.

What generally helps to reduce the allergen burden on atopic dogs?

Animals reacting to indoor allergens may need no other treatment if they are housed outside, e.g., in a kennel or cattery.

Regular washing removes allergens from the skin and this can be very helpful in controlling skins of canine atopic dermatitis.

Air conditioning and filtration systems are the most effective methods of allergen removal from the home.

In damp areas, dehumidifiers can help to reduce mite reproduction and mould growth.

Regular vacuuming and dusting, in conjunction with the periodic steam cleaning of carpets, also lower allergen levels.

How can I reduce exposure to house dust mites?

Mattresses, fabric-upholstered furniture and carpet are the major sources of house dust mites; indoor heating systems may assist aerosolization of mites and debris. Elimination of house dust mites is difficult but the following may help:

Reduce humidity.

Removing carpets may help but dust is then in direct contact with the dog's skin rather than deep within the pile.

Increased frequency of cleaning has not demonstrated a lower level of mite activity.

Wash bedding in hot water (>70°C/158°F); clean soft furnishings, bedding and living quarters frequently with damp cloth; place bean bags in the deep freeze to kill and denature the house dust mites (HDMs); thorough aeration and drying in sunlight will help to kill HDMs. Note that house dust mite faeces and dead mites are allergenic.

Ideally use high-efficiency particle air (HEPA) vacuum cleaners or at least ones with dust filters and/or fresh vacuum bags; keep pets out of rooms for 2-3 hours after vacuuming or cleaning; air rooms thoroughly.

Pets should be prevented from sleeping on furniture or beds; ideally, access to upstairs/bedrooms should be prevented entirely.

Consider removing 'dust-collectors' such as stuffed toys, upholstered furniture, books, newspapers and magazines.

Frequent grooming.

Provide plastic baskets and synthetic bedding (eg Vetbed®) that can be washed frequently at high temperatures, in uncarpeted, wood, vinyl or tile-floored rooms.

Sodium borate powder should be applied to carpets.

Use hypoallergenic waterproof casings for mattresses and pillows. Place a zippered plastic or HDM proof cover over the pet's bed.

The above activities may reduce mite numbers but residual allergen concentration may still cause clinical disease. Nevertheless, lowering the allergen burden is fundamental to long-term management.

How is exposure to storage mites reduced?

The significance of storage mites is uncertain. They may be associated with atopic dermatitis by cross reacting with house dust mites.

Check food bags for external damage before purchase.

Try not to buy more than a 30 day supply of food at a time.

High-quality food will have less particulate debris and may also come in re-sealable bags.

Store complete dry food in plastic containers with a tight-fitting lid, not in open bags or boxes. Do not store food in garages, sheds or cellars.

Do not feed dusty remnants of food at the bottom of the container.

Wash containers in hot (60°C/140°F) water and then dry completely before refilling.

Wipe the pet's mouth and lips after feeding with a damp sponge to remove food particles from the skin.

How is exposure to pollens reduced?

Plants that are wind-pollinated produce millions of pollen grains per floret. Conditions of high wind and low humidity promote the dissemination of pollen. Heavy prolonged rainfall 'cleans the air' but light rainfall at a time when airborne pollen numbers are high decreases convection and airspeed thus prolonging local exposure.

Confine the pet inside especially whilst mowing the lawn.

Restrict outdoor activities during times of high pollen concentrations especially during dawn and dusk when high pollen counts are forecasted.

Removal of some trees with heavy pollens may assist, e.g., pines, and wattles.

Rinse allergen from the skin surface using flowing water after exposure, eg after exercising in fields.

Avoid long grass and grass cuttings.

Keep weeds out of the garden and avoid having shrubs, etc near open windows/doors.

How is exposure to moulds reduced?

When indoor humidity levels get over 60%, mould allergens are more likely to be present hence reducing condensation and removing fabrics from that environment reduces mould exposure.

1. Avoid access to high humidity areas such as a bathroom, utility room, basement, conservatory, greenhouse, barn, etc.

Fig. 6: High humidity areas

2. Avoid large numbers of houseplants.

3. Avoid exposure to leaf litter, mulches, soil, rotting logs, grain bins/silos, hay/silage and compost bins.

Fig. 8: Some outside compound areas where moulds can be found

4. Avoid dusty foods.

How is exposure to epithelials (sheep wool, duck/goose/chicken feathers) reduced?

Limit exposure to the following that may contain animal allergens in households and vehicles:-

Beddings

Carpets

Soft furnishings

References

Tiffany, S., Parr, J. M., Templeman, J., Shoveller, A. K., Manjos, R., Yu, A., & Verbrugghe, A. (2019). Assessment of dog owners' knowledge relating to the diagnosis and treatment of canine food allergies. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne, 60(3), 268–274.

Declercq, J. (2000). A case of diet‐related lymphocytic mural folliculitis in a cat. Veterinary dermatology, 11(1), 75-80.

Leistra, M., & Willemse, T. (2002). Double-blind evaluation of two commercial hypoallergenic diets in cats with adverse food reactions. Journal of feline medicine and surgery, 4(4), 185-188.

Verlinden, A., Hesta, M., Millet, S., & Janssens, G. P. J. (2006). Food allergy in dogs and cats: a review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 46(3), 259-273.

Eigenmann, P. A. (2009). Mechanisms of food allergy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 20(1), 5-11.

Roudebush, P., & Cowell, C. S. (1992). Results of a hypoallergenic diet survey of veterinarians in North America with a nutritional evaluation of homemade diet prescriptions. Veterinary dermatology, 3(1), 23-28.

Ellwood C M & Garden O A (1999) Gastrointestinal immunity in health and disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 29 (2), 471-500 PubMed.

Hill P (1999) Diagnosing cutaneous food allergies in dogs and cats - practical considerations. In Practice 21 (6), 287-294 VetMedResource.

White S D (1998) Food allergy in dogs. Comp Cont Ed Prac Vet 20 (3), 261-269 VetMedResource.

Paterson S (1995) Food hypersensitivity in 20 dogs with skin and gastrointestinal signs. JSAP 36 (12), 529-534 PubMed.

Simpson J W (1995) Management of colonic disease in the dog. Waltham Focus 5, 17-22.

Fadok V A (1994) Diagnosing and managing the food-allergic dog. Comp Cont Ed Prac Vet 16 (12), 1541-1544 VetMedResource.

Halliwell R E W (1993) The serological diagnosis of IgE-mediated allergic disease in domestic animals. J Clin Immunoassay 16 (2), 103-108 VetMedResource.

Rosser E J (1993) Diagnosis of food allergy in dogs. JAVMA 203 (2), 259-262 PubMed.

Halliwell R E W (1992) Management of dietary hypersensitivity in the dog. JSAP 33 (4), 156-160 VetMedResource.

Kunkle G & Horner S (1992) Validity of skin testing for diagnosis of food allergy in dogs. JAVMA 200 (5), 677-680 PubMed.

Jeffers J G, Shanley K J & Meyer E K (1991) Diagnostic testing of dogs for food hypersensitivity. JAVMA 198 (2), 245-250 PubMed.

Scott D W (1978) Immunologic skin disorders of the dog and cat. Vet Clin North Am 8 (4), 641-664 PubMed.

Other Sources Of Information

Brostoff J & Hall A (1996) In: Immunology. 4th edn. Roti I, Brostoff J & Male D (eds). D Mosby, London. pp 15.

Wills J M & Halliwell R E W (1994) Dietary Sensitivity. In: The Waltham Book of Clinical Nutrition of the Dog and Cat. pp 167-188.

Reedy L M & Miller W H (1989) Allergic skin diseases of Dogs and Cats. W B Saunders, Philadelphia. pp 147-159.

Comments