Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Cats: Understanding, Diagnosis, and Management

- Dr Andrew Matole, BVetMed, MSc

- Nov 27, 2025

- 8 min read

What is Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)?

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant tumour arising from the squamous epithelium—the flat, thin cells that cover the skin and line body cavities (e.g., the oral cavity and nasal planum) and form areas such as paw pads, nail beds, ears, and eyelids. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one of the most common malignant tumours in cats. It is locally aggressive, often destructive, and, in advanced cases, life-threatening (Murphy, 2013). In cats, SCC typically affects two major sites, the skin (cutaneous SCC) and the oral cavity (feline oral squamous cell carcinoma, FOSCC). Cutaneous (skin) squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and feline oral squamous cell carcinoma (FOSCC) are both malignant tumours, but FOSCC is significantly more aggressive, with a much poorer prognosis. While SCC is treatable, especially if caught early, FOSCC is often diagnosed later and is highly invasive, with the sublingual (under the tongue) location having the worst prognosis.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) manifests in two major anatomical forms:

Cutaneous (skin) SCC is particularly prevalent in non-pigmented, sun-exposed areas such as the nasal planum, ear tips, and eyelids.

Oral SCC (feline oral squamous cell carcinoma, FOSCC) affects the mouth, jaws, tongue, or gingiva.

Early detection and prompt management are essential for improving patient outcomes.

How common is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)?

In the oral cavity, SCC is the most common malignant tumour in cats, accounting for roughly 70%–80% of oral neoplasms (cancers). On the skin, SCC accounts for about 15% of feline skin tumours in some series.

Who gets it? And when?

SCC is most commonly diagnosed in older cats, with median ages around 10–12 years (for the skin form) and around 12 years (for the oral form). There is no documented strong breed or sex predisposition, though white or lightly coloured non-pigmented-skinned cats are at a higher risk for the cutaneous form.

What triggers SCC?

The precise cause is multifactorial and not fully understood, especially for the oral form. Some important mechanisms and risk factors include:

For cutaneous SCC:

CCutaneous SCC commonly affects the nasal planum, ear tips, and eyelids, which are areas characterised by minimal pigmentation and sparse hair coverage (Swanson, 2020). Chronic ultraviolet (UV) light exposure is a major driver of skin SCC in non-pigmented or sparsely haired areas. Chronic UV exposure damages cellular DNA in squamous epithelial cells, leading to genetic mutations that lead to neoplastic transformation (Murphy, 2013).

Adapted from Alam & Ratner (2001)

For oral SCC (FOSCC):

Oral SCC (FOSCC) has a more complex aetiology. Researchers have investigated several environmental and viral factors. Proposed contributing factors include environmental carcinogens, exposure to household tobacco smoke, the use of flea collars, dietary influences (especially diets high in canned food or tuna), and chronic oral inflammation from dental diseases such as periodontal disease and gingivostomatitis, all of which may predispose individuals to oral SCC.

Still, evidence is limited (6.4% of 485 cats in one review had documented oral comorbidity). A study revealed that 35.2% (30/85) of FOSCC cats had a history of exposure to tobacco smoke (Sequeira et al., 2023). A critical review revealed that feline papillomavirus (FcaPV) DNA sequences were identified in 16.2% of FOSCC samples, although a conclusive causal relationship has yet to be established (Sequeira et al., 2023).

Table 1: Summary of Key Triggers/Risk Factors

Risk Factor | Explanation |

Chronic sun/UV exposure | Most common trigger |

Fair skin | Less melanin = less protection |

Older age | More cumulative exposure |

Chronic wounds/scars | Can become cancerous |

Immunosuppression | Weaker immune surveillance |

Smoking/chemical exposure | Especially in the mouth or lungs |

HPV (certain strains) | Linked to SCC in oral/genital regions |

What happens in the body?

Squamous cell carcinoma is a type of skin cancer, also known as epithelial cancer, that originates in squamous cells—flat cells located on the surface of the skin, mouth, nose, throat, lungs, and other organs. Consider squamous cells to be like tiles that cover and protect the body. When they become damaged—especially by long-term sun exposure—they may start behaving abnormally and turn cancerous.

SCC originates in the keratinocytes of the squamous epithelium. In cats, keratinocytes may undergo malignant transformation as a result of chronic irritation or genetic damage caused by UV exposure. Feline oral SCC tends to be highly locally invasive, frequently destroying underlying bone and soft tissue, infiltrating adjacent tissues, and rarely amenable to complete surgical excision. However, distant metastasis is relatively uncommon in cats with feline oral SCC (Pellin & Turek, 2016). Recent histopathological studies have shown that feline oral SCC exhibits biological behaviour similar to that of human head and neck SCC, including tumour cellular plasticity, invasiveness, and the presence of cancer stem-cell-like markers (Brandão et al., 2023).

How does squamous cell carcinoma appear?

Cutaneous SCC

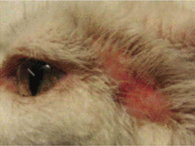

Clinical signs of cutaneous SCC may appear as a non-hairy, unpigmented area featuring a small scab, sore, ulcer, crusted lesion, or non-healing sores on sun-exposed regions such as the ear tips, eyelids, or nasal planum (Murphy, 2013). These lesions progress slowly and may initially be mistaken for chronic solar dermatitis. Cats may scratch or groom the affected area excessively.

Oral SCC

Oral SCC may present with symptoms such as excess drooling (ptyalism), halitosis (bad breath), difficulty or reluctance to eat, bleeding gums (gingival bleeding), tooth loss or loose teeth, facial or jaw swelling, and visible oral masses or ulcers in the mouth (Pellin & Turek, 2016) Lesions can affect the gums (gingiva), especially the maxilla or mandible, as well as the tongue, sublingual area, or tonsillar region. Tumours in the mandible are frequently proliferative, firm, and expansile, whereas lesions in the maxilla typically present as ulcerative and infiltrate adjacent tissue (Pellin & Turek, 2016). Late-stage cases may exhibit jaw deformity or difficulty in closing the mouth.

Diagnostic approach

Physical examination focusing on sun-exposed skin areas (cutis) and thorough oral examination (under sedation or anaesthesia if needed) for early lesions. For cutaneous SCC in high-risk sites, the assessment of tumour size, depth, and possible regional nodes aids the prognosis.

Biopsy & histopathological confirmation is the definitive diagnostic method; cytology may assist but is often less definitive (Swanson, 2020). Fine-needle aspiration cytology can suggest malignancy but is rarely definitive.

Diagnostic imaging may encompass skull and mandible radiographs and CT or MRI scans for oral squamous cell carcinoma to evaluate bone involvement, its extent, and surgical feasibility (Pellin & Turek, 2016). Diagnostic imaging is crucial for staging and treatment planning. Thoracic imaging is recommended to rule out metastasis, although distant spread is rare (Murphy, 2013).

A CT scan of a cat's head showing maxillary bone (upper jaw) involvement of SCC

Treatment and Prognosis

Cutaneous SCC

The gold standard and often first-line treatment for cutaneous SCC is wide surgical excision, ideally performed with 1–2 cm margins (Swanson, 2020). If complete excision is achieved, long-term control or cure is possible.

When surgery is not feasible, alternative treatment modalities include cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy (especially for nasal planum cases), laser ablation, or strontium-90 plesiotherapy (Murphy, 2013).

In one study of cats with nasal planum SCC treated with an accelerated radiation protocol (10 × 4.8 Gy in one week), the median disease-free interval was about 916 days and the overall survival was 902 days, with tumour volume being a key prognostic factor (Bray et al., 2017); tumour volume significantly influenced outcome (Gasymova et al., 2017).

The prognosis for cutaneous SCC is generally satisfactory to fair, especially when diagnosed early and completely excised (Swanson, 2020).

Oral SCC (FOSCC)

Oral SCC is significantly more aggressive, making treatment challenging. By the time of diagnosis, the tumour is often advanced, and many lesions have invaded the bone, which makes complete surgical removal difficult (Pellin & Turek, 2016).

In the initial cases, treatment options include mandibulectomy, maxillectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy; however, the overall prognosis remains unfavourable. Median survival times are often less than six months, and the one-year survival rates rarely exceed 10% (Loomis, 2020).

Novel therapeutic approaches, such as the combination of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (toceranib) with radiation, have shown limited improvement in patient outcomes, and most cats did not benefit significantly from these treatments (Javle et al., 2021).

Preventive Measures and Early Detection

Preventive strategies are vital for high-risk cats:

Keep white- or light-colored cats indoors during peak daylight hours or provide shade to minimise UV exposure and reduce the risk of cutaneous SCC.

Apply pet-safe sunscreen to the ear tips and nasal planum of cats if outdoor exposure is unavoidable.

Schedule regular veterinary oral health check-ups to ensure early detection of oral lesions. Dental cleanings and oral exams under sedation may help identify early masses.

Watch for subtle signs: a persistent scab or sore on the ear tip, eyelid, or nose is a sign of skin SCC, while drooling, reluctance to eat, bad breath, oral discomfort, and weight loss are signs of oral SCC. Early diagnosis significantly increases the chances of successful treatment (Swanson, 2020).

Understand the prognosis: While some forms (especially early skin lesions) have favourable chances with timely treatment, oral SCC remains challenging. Early diagnosis improves options.

Discuss the quality of life: ensure that any treatment plan prioritises the cat’s comfort and that palliative goals are considered when a cure is unlikely.

Conclusion

SCC is a malignant tumour of squamous epithelium common to cats, both on the skin and in the mouth. Cutaneous SCC is often driven by UV exposure in non-pigmented skin; oral SCC has more complex multifactorial risk factors, including possible viral, environmental, dietary and inflammatory components. Squamous cell carcinoma is a serious but potentially manageable cancer in cats when identified early. Cutaneous SCC responds well to surgical excisions or localised radiation. In contrast, oral SCC remains a challenging disease with limited curative options, which underscores the value of early detection and preventive care. Diagnosis is via biopsy/histopathology; imaging is important, especially for oral cases. Treatment and prognosis diverge significantly: cutaneous SCC can have positive outcomes if detected early and removed completely; oral SCC remains highly aggressive with poor long-term outcomes in many cases. Early detection, routine oral exams, client education about sun exposure, and attention to subtle signs in older cats are vital for improving patient outcomes. Veterinary practitioners should maintain a high index of suspicion for SCC in older cats, especially those with sun-exposed skin or chronic oral disease, and guide pet owners through realistic treatment options and quality-of-life decisions.

References

Alam, M., & Ratner, D. (2001). Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(13), 975–983. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200103293441306

Beckman, B. D. (2025.). Oral squamous cell carcinoma in cats. Veterinary Dentistry Dental Cases. Retrieved November 26, 2025, from https://veterinarydentistry.net/oral-squamous-cell-carcinoma-cats/

Bray, J. P., Polton, G. A., Munday, J. S., & Dobson, J. M. (2017). Treatment of feline nasal planum squamous cell carcinoma with an accelerated radiation protocol. BMC Veterinary Research, 13(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1018-3

Brandão, J. F., Sousa, M., & Lopes, C. (2023). Comparative pathology of feline head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and human oral carcinoma. Pathogens, 12(11), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12111288

Gasymova, E., Meier, V., Guscetti, F. et al. Retrospective clinical study on outcome in cats with nasal planum squamous cell carcinoma treated with an accelerated radiation protocol. BMC Vet Res 13, 86 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1018-3

Gow, D. (2010). Feline squamous cell carcinoma. Companion Animal, 15(5), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-3862.2009.tb00416.x

Javle, M., Shoemaker, A., & Borrego, C. (2021). Use of toceranib phosphate in feline oral squamous cell carcinoma following radiation therapy: A retrospective study. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 23(9), 875–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X211314343

Loomis, M. (2020). Feline oral squamous cell carcinoma: Clinical presentation and management. Today’s Veterinary Practice, 10(2), 46–55. https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/oncology/feline-oral-squamous-cell-carcinoma/

Murphy, S. (2013). Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in the cat: Risk factors, treatment and outcome in 61 cases. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 15(4), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X13483238

Pellin, M., & Turek, M. (2016). A review of feline oral squamous cell carcinoma. Today’s Veterinary Practice, 6(4), 32–39. https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/10/2016-1112_FelineCancer_NO-AD.pdf

Sequeira, I., Niza, M. M. R. E., & Requicha, J. F. (2023). Feline oral squamous cell carcinoma: A critical review of etiologic factors. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10, 9609408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.9609408

Swanson, C. (2020). Feline skin (cutaneous) squamous cell carcinoma. Veterinary Specialists of the Rockies. https://www.vetspecialists.com/vet-blog-landing/animal-health-articles/2020/04/14/feline-skin-squamous-cell-carcinoma

Comments