Mast Cell Tumours (Mastocytomas) in Companion Animals

- Dr Andrew Matole, BVetMed, MSc

- Aug 15, 2025

- 9 min read

your pet Introduction

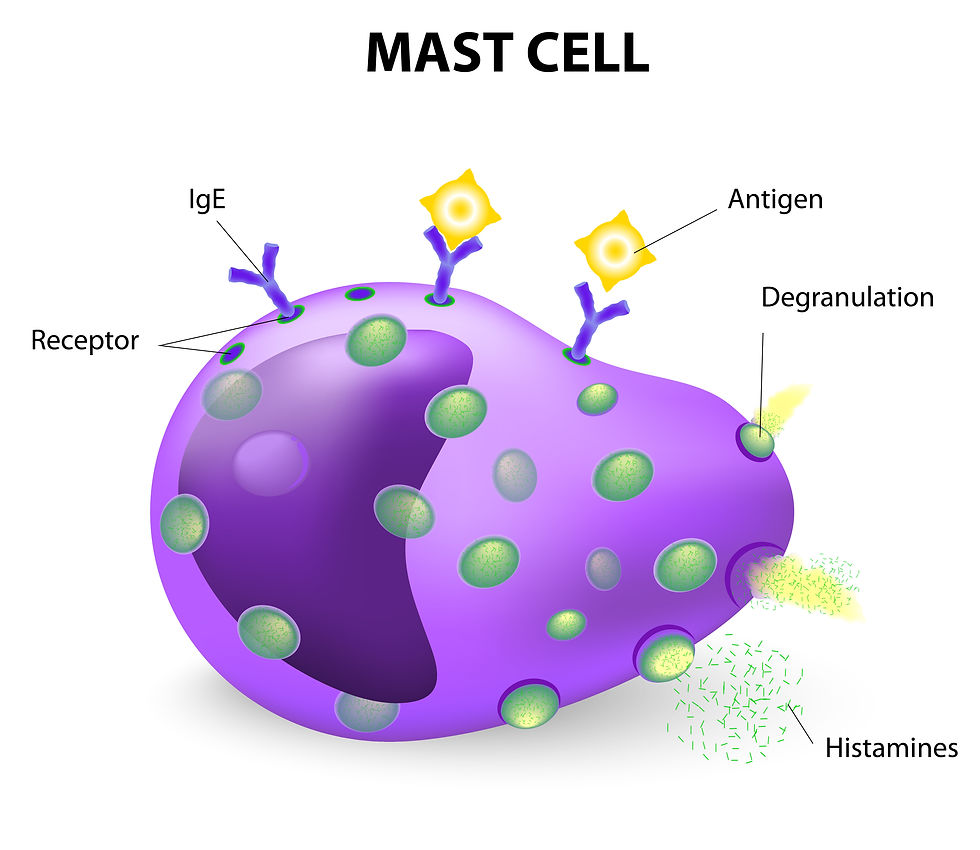

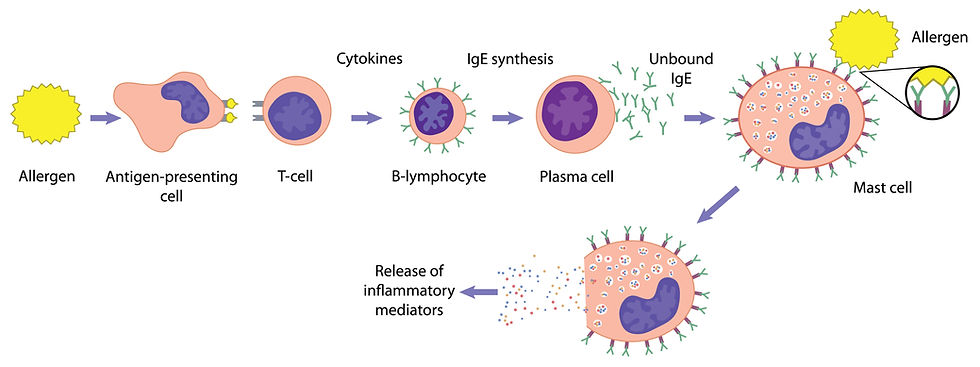

Mast cells are normal immune cells commonly found in connective and mucosal tissue throughout the body. They are characterised by large cytoplasmic granules and specific cell surface receptors, and are found particularly in tissues within the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory system. The granules contain chemical substances that play a crucial role in allergic and inflammatory responses. The substances released from the granules when the mast cells are triggered are chemical messengers that include proteases, histamines, serotonin, heparin, cytokines, growth factors, and other inflammatory mediators. When these cells multiply abnormally, they can form tumours either in the skin or internally.

What Are Mast Cell Tumours (MCTs)?

Mast cell tumours (MCTs) are abnormal growths of mast cells and are among the most common skin cancers in dogs and can also affect cats. In dogs, MCTs can present in a wide variety of ways: from small, innocuous bumps to ulcerated or firm masses. Such tumours may suddenly swell, redden, or itch due to mast cell degranulation—that is, the release of histamine and other chemicals when these cells are irritated or handled (de Nardi et al., 2022). While many MCTs are treatable, some can behave aggressively and metastasise to other organs. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are key to achieving a positive outcome. MCTs account for 7–21% of all cutaneous tumours in dogs and represent one of the most commonly diagnosed skin malignancies in small animal practice.

How Do Mast Cell Tumours Appear?

MCTs can appear differently from one animal to another, making professional veterinary assessment critical. They can look like almost anything:

A firm, elevated mass on or beneath the skin—sometimes accompanied by hair loss—may appear as a small “bug-bite”–like bump, a smooth pink nodule, an ulcerated growth, or a solid swelling beneath the surface.

Fluctuating size or rapid growth

Local inflammation (Redness), ulceration, or itchiness

Gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting, diarrhoea or lethargy (due to histamine release)

Gastrointestinal ulcers in advanced cases

Systemic symptoms if metastasis occurs

MCTs are known as “the great pretenders” because their appearance varies greatly, and because of this, every new lump should be checked.

Why do Mast Cell Tumours sometimes swell or itch?

Mast cells are a type of immune cell that plays a crucial role in the body's allergic responses and defence mechanisms. They are primarily known for their storage of various chemicals, including histamine, which is a potent mediator involved in inflammatory responses. In the context of tumours, particularly those that are associated with mast cells, handling or irritating the tumour can trigger a process known as “degranulation.” This occurs when mast cells release their stored chemicals into the surrounding tissue, which can lead to a range of acute reactions. When degranulation happens, the tumour mass may exhibit noticeable changes, such as suddenly puffing up, which can be attributed to the influx of fluid and inflammatory cells into the area.

Additionally, the affected region may become reddened due to increased blood flow, a result of the vasodilatory effects of histamine. This response can also lead to intense itching, which is particularly distressing for the animal. In more severe cases, the systemic effects of degranulation can manifest as gastrointestinal disturbances, including vomiting and diarrhoea. These symptoms arise because histamine can affect the gastrointestinal tract, leading to increased gastric acid secretion and altered gut motility. Moreover, chronic irritation and inflammation can predispose the animal to more serious conditions, such as stomach ulcers, which can result from the erosion of the stomach lining due to excessive acid production.

Which breeds are at a higher risk of developing MCTs?

Any pet can develop an MCT, but certain breeds are more predisposed than others, with Shar-Peis being more likely to develop more complex and unpredictable tumours. While less common in cats, MCTs do occur in older cats. Cutaneous (Skin) MCTs usually occur on the head or neck, while visceral forms can involve the spleen or gastrointestinal tract (Wiles et al., 2016).

In canines, middle-aged to older dogs (average age: 8–10 years) are most commonly affected. Many breeds of dogs are predisposed to mast cell tumours and include Australian Cattle Dog, Beagle, Boxer, Boston Terrier, English Bull Terrier, Bullmastiff, Cocker Spaniel, Dachshund, English Bulldog, Fox Terrier, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever, Pug, Rhodesian Ridgeback, Schnauzer, Shar-Pei, Staffordshire Terrier, and Weimaraner as shown in the table below.

How do we diagnose a mastocytoma?

Diagnosis typically begins with a fine-needle aspirate (FNA), a minimally invasive technique that can often identify mast cells under the microscope by their characteristic granules. It involves extracting a sample of cells with a needle. Mast cells appear as large, round cells with purple granules under the microscope. When MCT is confirmed, a biopsy is used for definitive grading (low, intermediate, or high). A part or all of the tumour is removed surgically and sent to a pathologist who then “grades” it under the microscope to estimate behaviour using the Patnaik or Kiupel systems, which indicate tumour aggressiveness. The Kiupel two-tier system (low vs. high grade) is now widely used due to its reliability in predicting outcomes. Besides, extra tests such as mitotic counts or c-KIT mutation status (specific genetic changes) are assessed in selected cases because specific DNA changes in the KIT gene are linked with more aggressive disease and can guide targeted therapy. They can also inform prognosis and the choice of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

Staging: has the Mastocytoma spread?

For the assessment of whether the tumour has spread or not, the following are recommended:-

Complete blood count (CBC)

Serum chemistry

Abdominal ultrasound

Thoracic radiographs

Lymph node aspiration of the nearest lymph node. Spread to lymph nodes generally worsens prognosis and may change the treatment plan.

In select cases, liver/spleen sampling.

Treatment Options

Treatment depends on tumour grade, location, and whether it has spread.

Surgical Removal

Surgery is the treatment of choice for localised, low-grade MCTs with wide margins around and below the mass because microscopic “fingers” can extend past what is seen or felt. (typically 2–3 cm laterally and including deep tissue, anatomy permitting). Margin decisions are tailored to tumour grade, size, and location. Clean (tumour-free) margins lower the chance of regrowth.

Targeted Therapy (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors – TKIs)

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are a form of targeted cancer therapy designed to block specific cellular signals that drive tumour growth. In mast cell tumours (MCTs), a common target is the KIT receptor, which is often abnormally activated due to mutations in the c-KIT gene. This abnormal activation stimulates mast cells to multiply uncontrollably. TKIs attach to the KIT receptor’s active site, preventing it from transmitting “grow and divide” signals. This can slow or stop tumour progression and, in some cases, shrink the tumour. The commonly used TKIs are Toceranib phosphate (Palladia®) and Masitinib mesylate (Masivet®).

The KIT receptor (also called CD117) is a protein found on the surface of certain cells, including mast cells, which plays a key role in cell growth, survival, and function.

Chemotherapy & steroids.

These are commonly indicated as adjuvant (supportive) therapy for high-grade tumours, metastatic, positive lymph nodes, unresectable, or incomplete excision, balancing benefits and side-effects for the pet.

Drugs include:

Vinblastine

Lomustine

Cyclophosphamide

Prednisone

Toceranib phosphate (Palladia®), especially in cases involving c-KIT mutations. It is an oral anti-cancer drug shown to be effective in cats and dogs

Radiation Therapy

When surgical margins are incomplete or tumours are in anatomically challenging locations where wide surgery isn’t possible (e.g., muzzle, distal limbs), hence cannot be completely removed surgically, focused radiation offers excellent local control. Radiation is also used as adjunctive therapy for residual disease after surgery because mast cells are generally sensitive to focused radiation.

Targeted Intratumoural Therapy

For certain superficial, non-metastatic MCTs, a single injection of Tigilanol tiglate (Stelfonta®) directly into the tumour induces destruction of the tumour. The wounds then heal over several weeks under a strict after-care plan. Not every mass is a candidate. Tigilanol tiglate (Stelfonta®) has shown an 88% complete response rate after two doses, the second dose typically administered 28 days (four weeks) later.

Supportive Medications

Because of their potential to release histamine, dogs with MCTs often receive H1 antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine) for itch control and H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors (e.g., famotidine or omeprazole) to manage symptoms and protect the stomach before and after treatment. The antihistamines control histamine-related effects and the gastroprotectants (e.g., omeprazole) prevent ulcers. Steroids (e.g., prednisolone) help shrink the tumour and reduce inflammation

Follow-up examinations are usually done every 2–3 months initially with intervals widening if all is well.

Special Considerations for Cats

Feline MCTs behave differently. Cutaneous tumours are often cured by surgery and often have a good prognosis post-surgery. Splenic MCT commonly causes lethargy, weight loss and a big spleen; splenectomy (removal of the spleen) is the treatment of choice and can be very effective. Intestinal MCTs carry a more guarded prognosis.

What’s the prognosis?

Prognosis is influenced by several pieces of the puzzle working together:-

Tumour grade (Kiupel low vs high) and mitotic activity,

Surgical margins (clean vs incomplete margins after surgery),

Size/location (lymph node, liver/spleen, etc), and whether metastasis (spread) has occurred or

whether c-KIT mutations (molecular markers) are present.

Many low-grade mastocytomas are cured with surgery alone. One good surgery with clean margins after removal has an over 90% survival rate at 2 years. High-grade tumours, or those with spread (metastatic), are more unpredictable and may carry a guarded to poor prognosis, and often require aggressive multimodal treatment combining surgery, systemic therapy, and close follow-up (Kiupel et al., 2011). In cats, cutaneous MCTs generally have a favourable prognosis, especially if the tumour is solitary and surgically removed, while splenic or intestinal MCTs can be more serious (Wiles et al., 2016).

What You Can Do as a Pet Owner

Perform monthly skin checks, especially in at-risk breeds

Have all new lumps checked by your veterinarian

Avoid touching, squeezing, or aggressively manipulating suspect lumps.

Use an Elizabethan collar to prevent your pet from licking, chewing, or scratching the lump(s).

Keep a record (a lump diary): take weekly photos and measurements.

Watch and report any changes or symptoms in size, colour, like sudden redness, swelling, itchiness, ulceration, vomiting, diarrhoea, or black stools promptly to your vet.

Follow through with all recommended diagnostics and follow-up appointments/rechecks after surgery or treatment.

References

American Animal Hospital Association. (2024). Types of cancer in pets. AAHA.

American Animal Hospital Association. (2016). Oncology guidelines for dogs and cats.

Blackwood, L., Murphy, S., Buracco, P., De Vos, J. P., De Fornel-Thibaud, P., Hirschberger, J., … & Argyle, D. J. (2012). European consensus document on mast cell tumours in dogs and cats. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology, 10(3), e1–e29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5829.2012.00341.x

Breed risk: Shoop et al., 2015; Śmiech et al., 2019. BioMed CentralPMC

Casanova, B., et al. (2021). Kiupel two-tier grading system: Improved prognostic accuracy. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation.

Dąbrowska, N., et al. (2024). Canine mast cell tumours: Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Veterinary Molecular and Regional Research.

de Nardi, A. B., et al. (2022). Diagnostics, prognosis, and treatment of canine cutaneous mast cell tumours—a consensus review. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology.

Dobson, J. M., & Scase, T. J. (2007). Advances in the diagnosis and management of cutaneous mast cell tumours in dogs. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 48(4), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2006.00212.x

DVM360. (2022). Canine cutaneous mast cell tumors: Current concepts in patient management. dvm360.com.

Feline splenic MCT and splenectomy: Lee et al., 2021; Henry, 2012 review. PMC+1

Henry, C. J. (2012). Feline mast cell tumours: A clinical review. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery.

Hoffmann, U., & Mauer‑Popp, K. (2024, November 6). Mast cell tumor in dogs: How to recognize and treat this dangerous disease. Bellfor. https://uk.bellfor.info/mast-cell-tumor-in-dogs

Horta dos Santos, E., et al. (2017). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in canine mast cell tumour therapy. Veterinary Oncology Journal.

IDEXX Laboratories. (n.d.). Canine mast cell tumour overview. IDEXX.com.

Intratumoural tigilanol information: Stelfonta site. Stelfonta

Lee, A., et al. (2021). Splenic mast cell tumours in cats: Clinical outcomes after splenectomy. Feline Surgical Journal.

Kiupel two-tier grading & prognostic value. Michigan State Univ. VDL; Casanova et al., 2021. MSU Veterinary MedicinePMC

Kiupel, M., Webster, J. D., Bailey, K. L., Best, S., DeLay, J., Detrisac, C. J., ... & Yager, J. A. (2011). Proposal for a 2-tier histologic grading system for canine cutaneous mast cell tumors to replace the Patnaik system: Prognostic and diagnostic implications. Veterinary Pathology, 48(1), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985810386469

London, C. A., Hannah, A. L., Zadovoskaya, R., Chien, M. B., Kollias-Baker, C., Rosenberg, M., … & Modiano, J. F. (2009). Phase I dose-escalating study of SU11654, a small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in dogs with spontaneous malignancies. Clinical Cancer Research, 9(7), 2755s–2768s.

Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. (n.d.). Prognosis of canine cutaneous mast cell tumors. MSU VDL.

Peri-operative antihistamines/acid suppression: dvm360 clinical review; European consensus note; TVP 2024 update. DVM360Wiley Online LibraryToday's Veterinary Practice

Stelfonta®. (n.d.). Stelfonta treatment day overview. stelfonta.com.

Śmiech, A., et al. (2019). Breed predisposition to mast cell tumours in dogs. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology.

Surgical margins & oncology guidelines: AAHA Oncology Guidelines (2016); margin literature summary. AAHADove Medical Press

TKIs & dosing examples: Horta dos Santos et al., 2017. PMC

Today’s Veterinary Practice. (2024). Simplifying the approach to canine mast cell tumors. todaysveterinarypractice.com.

VCA Animal Hospitals. (2024). Mast Cell Tumors in Dogs. Retrieved from https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/mast-cell-tumors-in-dogs

Webster, J., et al. (2006). KIT mutations in canine mast cell tumours. Journal of Veterinary Pathology.

Wiles, V., Hohenhaus, A., Lamb, K., Zaidi, B., Camps-Palau, M., & Leibman, N. (2016). Retrospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate (Palladia) in cats with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 19(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X15622237

Comments