What is Solar Dermatitis?

- Dr Andrew Matole, BVetMed, MSc

- Jun 25, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 27, 2023

What is Canine Solar Dermatitis?

Canine solar dermatitis, sometimes known as chronic sun damage to the skin, is a common dermatological condition that affects poorly pigmented skin through phototoxicity in hot, sunny climates. Even in temperate climates, it can also affect animals that dwell at high altitudes or spend a lot of time outdoors. In all climatic conditions, solar dermatitis has no age predisposition, and it can start at any age depending on sun exposure. Solar dermatitis can start early with symptoms observed in animals as young as 3 months old and skin abnormalities as early as 3 years of age, even though 6 years of age is the most usual age at which veterinarians observe skin changes. Animals with scars, depigmented skin are also predisposed to sun-related skin problems.

What are the general predisposing factors to solar dermatitis?

The general risk factors for solar dermatitis in canines and felines include a lack of pigmentation, a lack of hair, sunbathing, and the tendency for specific breeds to be more pigment deficient. Higher elevation, white or light-colored concrete, can cause animals kept indoors be exposed to enough sunshine to develop solar dermatitis.

Which breeds are more predisposed to Solar Dermatitis?

Nasal solar dermatitis is more common in Australian Shepherds while the dermatitis involving the trunk and extremities is more likely to affect Mexican hairless dogs, Dalmatians, American Staffordshire terriers, white Boxers, Pit Bull Terriers, White Bull Terriers, American Bulldogs, Whippets and white cats can be affected. Any animal with white or lightly pigmented hair and skin is at risk.

How does Solar Dermatitis develop?

About 40% of the solar spectrum is made up of visible light rays (400–700 nm), 50% is made up of infrared light rays (700–20,000 nm), and 9% is made up of ultraviolet (UV) light rays (100 to 400 nm) that are divided into UVA and UVB rays.

In comparison to UVB rays, UVA rays (320 to 400 nm) penetrate the skin more deeply and are linked to photosensitivity reactions. In addition to directly harming keratinocytes, prolonged exposure to shorter wavelength UVB solar rays (290 to 320 nm) also induces follicular damage leading to superficial skin blood vessel dilation and leakage of leukocytes into the affected area. This condition is known as phototoxicity (sunburn). Increases in inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes as well as hazardous oxygen intermediates sustain and enhance tissue injury after sun damage of epithelial tissues.

Sun damage that is sustained over time results in keratinocyte growth, mutagenesis, atypia, and premalignant actinic keratosis that can progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Since pigmented skin contains melanin, which absorbs UV rays, actinic damage and deeper UV light penetration are typically avoided. About 45% more solar energy is absorbed by black skin than by white skin. In comparison to visible radiation, which can penetrate the skin and cause thermal injury and necrosis, UV light makes only a small portion of the thermal or heat burden.

What are the presenting signs of solar dermatitis?

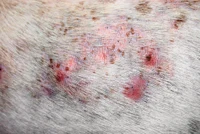

Solar dermatitis can affect the extremities and trunk as well as the nose. Erythema and scaling that later develop into crusting and ulcerations characterize the nasal forms. The form that develops on the body starts off as comedones and erythema before developing ulcerations and crusting. The condition is persistent and gets worse over time when exposed to sunshine. Solar dermatitis can mimic other skin conditions like allergies or pyoderma, causing delay in diagnosis and treatment until irreparable damage or skin cancer develops. There is always the lack of marked pruritus (itchiness) of the skin and the distribution of the lesions is such that they spare pigmented areas.

What are the clinical signs of solar dermatitis?

Solar dermatitis symptoms can differ. Before obvious scabbing and peeling appear, early symptoms of the illness might be as modest as erythema and fine scaling. Cats with advanced signs of the illness may fold their pinna or turn their heads in agony while dogs with severe disease frequently have the recognizable up-and-down, bumpy texture you feel when rubbing your hands over the affected skin. The depressions are areas that have been scarred, and the elevations are active inflammation locations. Sun damage can affect other locations as well as the dorsal and lateral trunk and lateral limbs. It typically affects nonpigmented, sparsely hairy areas such the flank, inguinal and axillary areas, and the dorsal nose.

Lesions may be worse on the side of the body that has been exposed to the sun for a longer period in dogs that like to sleep on one side. The amount of skin damage depends on the duration and the intensity of the sun exposure. Erythematous, scaly lesions that may be painful are the first symptoms of actinic injury. Dermal fibrosis, follicular cyst development, and actinic folliculitis are all brought on by prolonged sun exposure. There is frequently a clear distinction between damaged nonpigmented skin and normal skin with protective pigment in dogs. Damaged areas from prolonged sun exposure thicken and scar, developing comedones, erosions, ulcers, crusts, and draining tracts. Bacterial secondary pyoderma is frequent. Skin cancers such squamous cell carcinoma, hemangiomas, and cutaneous hemangiosarcoma may develop because of exposure to the sun. The itch associated with solar dermatitis is typically minor, unlike that in dogs with allergic dermatitis, even though affected dogs may lick the damaged areas. However, some dogs may also experience concomitant allergies and solar dermatitis.

How is Solar Dermatitis diagnosed?

When determining the patient's clinical signs and signalment for solar dermatitis, it's important to rule out any other potential causes of scaly, erythematous dermatitis, or folliculitis (e.g., bacterial, Demodex species, and dermatophyte infections). Whenever skin lesions don't respond to empiric therapy, there is likely to be solar dermatitis, and more investigations are required. The final step in diagnosing solar dermatitis and sun-induced neoplasia is skin biopsy and histology. Systemic antibiotics may be advised for two to three weeks prior to biopsy, depending on the severity of the secondary bacterial infection, to make sure that infection does not affect histologic interpretation. Clearing secondary skin infection also improves the chance that skin lesions picked for biopsy were caused by the sun rather than an infection. Biopsy can be performed by administering lidocaine locally and obtaining multiple skin punch or excisional biopsy samples of different lesions.

What conditions are to be differentiated from Solar dermatitis?

Depending on where the lesions are located, it is necessary to distinguish between other skin disorders and Solar Dermatitis. Other conditions that should be ruled out in cases of face or nasal dermatoses include Squamous cell carcinoma, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Pemphigus erythematosus, Discoid lupus erythematosus, and Drug eruption. Demodectic mange, allergic contact dermatitis, bacterial folliculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and drug eruption are some more disorders that should be ruled out when it comes to body lesions.

How is Solar Dermatitis treated?

Preventing canine solar dermatitis is the best course of action. Owners of vulnerable pets must comprehend the significance of avoiding the sun from an early age. Importantly, sun avoidance cannot be replaced by oral or topical drugs when it comes to treating or preventing solar dermatitis.

Reducing sun exposure

Reducing sun exposure is the recommended treatment for solar dermatitis by keeping the dog indoors during the day, especially between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m., which is considered the most intense UV radiation time.

If some sun exposure is unavoidable, then frequent (twice a day) topical application of a waterproof, high-SPF sunscreen (a product with an SPF > 30 absorbs more than 92% of UVB rays) that is labeled as safe for babies and that protects against UVA and UVB rays is indicated.

Although zinc toxicity is a common concern, problems resulting from sunscreen ingestion are rarely observed as a dog or cat would have to ingest a massive quantity (0.7 to 1 g/kg) to experience toxicosis, which is close to impossible with appropriate use. Having the dog wear a T shirt or a dog sun suit sewn using sun-blocking fabric available for people may help decrease sun exposure though it is often impossible to cover all at-risk areas of the skin.

Beta-carotene or acitretin

Early cases of solar dermatitis may benefit from the combination of oral glucocorticoids at anti-inflammatory levels and 30 mg of beta-carotene taken twice daily for 30 days, followed by 30 mg daily for life. Oral retinoids, which are more effective and less toxic than vitamin A, include acitretin, and can lessen skin damage when given at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg orally every 24 hours.

Retinoids may have adverse effects such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, mucocutaneous lesions, nausea, diarrhea, musculoskeletal problems, triglyceride increases, and hepatotoxicity; hence, careful monitoring is required, within four to six weeks, retinoids should provide a good clinical response. The frequency of medicine can then be decreased to every other day, and systematic use should be avoided as retinoids are also incredibly teratogenic. A positive clinical response to retinoids should be noted within four to six weeks. At that point, the frequency of medication can be reduced to an alternate-day basis.

Vitamin A

Oral vitamin A has been used anecdotally for canine solar dermatitis due to the cost of retinoids. Dogs should not get more than 400 IU/kg/day of oral vitamin A, and patients should be monitored for any side effects similar to those indicated for retinoids.

Imiquimod

In dogs, the mechanism of action of a topical immunomodulator like imiquimod cream (Aldara 5% cream), a retinoic acid also used to treat warts, is to induce local antitumor and antiviral immune responses by stimulating lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages. For four to 16 weeks, affected areas receive two to three applications of imiquimod cream per week. The treatment area shouldn't be greater than 2 × 2 inches, and the cream shouldn't be applied close to the lips, nose, or eyes because it may irritate the skin. After eight hours, the cream is gently removed with mild soap and water.

Every other day is recommended for imiquimod therapy. Localized symptoms at the application site include redness, crusting, burning, and itching.

Pentoxifylline

Pentoxifylline can be used to speed up the healing of wounds and enhance blood flow to a damaged skin. The basic dosage is 25 mg/kg twice daily (BID) orally but dosages of 10-35 mg/kg twice daily (BID) to 25 mg/kg thrice daily orally with food have been reported in literature and responses are thought to be better at higher doses but side effects may be significant.

Treatment may be needed for 1-3 months before response is seen. Even with prolonged use, it rarely causes negative effects which may include seizures, hypotension, unconsciousness, agitation, fever, somnolence, gastrointestinal distress (vomiting, inappetence), excitement, nervousness and ECG changes in humans.

Carbon dioxide laser

Comedones and other diffuse lesions can be removed with a carbon dioxide laser, helping to exfoliate and reveal healthy skin.

Surgery

It is required to surgically remove any sites that have pre-neoplastic alterations.

How is Solar Dermatitis Monitored?

Prior skin damage can still proceed to skin neoplasia months or years after exposure, even with sun protection. Once skin neoplasia has developed, it should be aggressively removed surgically or treated with laser therapy. Additionally, it's important to check for metastases to draining lymph nodes and internal tissues if there are sizable or invasive tumors present.

References

Alomar A, Bichel J, McRae S. Vehicle-controlled, randomized, double-blind study to assess safety and efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream applied once daily 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment of actinic keratoses on the head. Br J Dermatol 2007; 157:133-141.

Bernhard JD, Pathak MA, Kochevar IE, et al. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al., eds. Dermatology in general medicine. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co, 1987;1481-1507.

Breen P T (1972) Nasal solar dermatitis. Vet Med Small Anim Clin 67 (6), 652-653 PubMed.

Coyner, K. (2007, August 1). Diagnosis and treatment of solar dermatitis in dogs. Retrieved June 2023, from DVM360: https://www.dvm360.com/view/diagnosis-and-treatment-solar-dermatitis-dogs

Coyner, K. (2020). Distinguishing Between Dermatologic Disorders of the Face, Nasal Planum, and Ears: Great Lookalikes in Feline Dermatology. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 50(4), 823-882.

Frank L A, Calderwood-Mays M B, Kunkle G A (1996) Distribution and appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis of clinically normal dogs and dogs with solar dermatitis and other dermatoses. Am J Vet Res 57 (2), 178-181 PubMed.

Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, et al. Skin diseases of the dog and cat: Clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2005;399-401.

Hruza LL, Pentland AP. Mechanisms of UV-induced inflammation. J Invest Dermatol 1993; 100:35S-41S.

Ishii Y, Kimura T, Itagaki S, Doi K (1997) The skin injury induced by high energy dose of ultraviolet in hairless descendants of Mexican hairless dogs. Histol Histopathol 12 (2), 383-389 PubMed.

Keller KL, Fenske NA. Use of vitamins A, C, and E and related compounds in dermatology: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 39:611-625.

Kimura T, Doi K. Responses of the skin over the dorsum to sunlight in hairless descendants of Mexican hairless dogs. Am J Vet Res1994; 55:199-203.

Korman N, Moy R, Ling M, et al. Dosing with 5% imiquimod cream 3 times per week for the treatment of actinic keratosis: results of two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trials. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:467–473.

Mason K. Actinic dermatosis in dogs and cats, in Proceedings. Annu Meet Eur Soc Vet Dermatol Eur Coll Vet Dermatol 1997,67.

Mason KV. The pathogenesis of solar induced skin lesions in bull terriers, in Proceedings. Annu Member Meet Am Acad Vet Dermatol Am Coll Vet Dermatol 1987; 12.

Medleau LM, Hnilica KA. Small animal dermatology: A color atlas and therapeutic guide . Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2005.

Scheuplein RJ. Mechanism of temperature regulation in the skin. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al., eds. Dermatology in general medicine. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co, 1987;347-357.

Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. Muller and Kirk's small animal dermatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2001;1073-1080.

Yankell S L, Khemani L, Dolan M M (1970) Sunscreen recovery studies in the Mexican hairless dog. J Invest Dermatol 55 (1), 31-33 PubMed.

Comments